This article appears in the fall 2022 issue of University of Denver Magazine. Visit the magazine website for bonus content and to read this and other articles in their original format.

Green roofs—idyllic retreats located at the top of buildings—have become a popular way to beautify urban spaces and provide environmental benefits to structures and the spaces around them. Not to be left out, the University of Denver incorporated a green roof into the design of its new Community Commons building. The expansive green space on the fourth-floor exterior deck nods to the beauty of Colorado’s native plants and the University’s sustainability goals.

The Community Commons’ green roof is an impressive feat of urban landscaping, featuring several garden beds that surround a floor-to-ceiling glass pavilion. Among the hardy plants in those beds: Tall native grasses that bend in the wind and provide a picturesque foreground for the foothills of the Rocky Mountains to the west and the downtown Denver skyline to the north.

This eye-popping view is intentional, says University architect Mark Rodgers, noting that the green space is meant to “cut out the foreground of the houses and built structures; and [one can] just see the tops of trees, and then the mountains beyond and hopefully the beautiful sunsets.”

Aesthetics aside, the green roof complements the University’s plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030. Green roofs can help keep buildings cool, reduce building energy use and absorb rainwater. Just as important, any plants incorporated into the roof can capture and store carbon dioxide, considered one of the major contributors to climate change.

The Community Commons’ green roof isn’t the first of its kind on campus. Technically, Rodgers says, DU has three green roof spaces; the other two are located at the Daniels College of Business and at Nelson Hall.

“However, both of those roofs I would consider to be not anything close to the complexity, the ambition or the public-natured showcasing that we’ve done at the Community Commons,” he says.

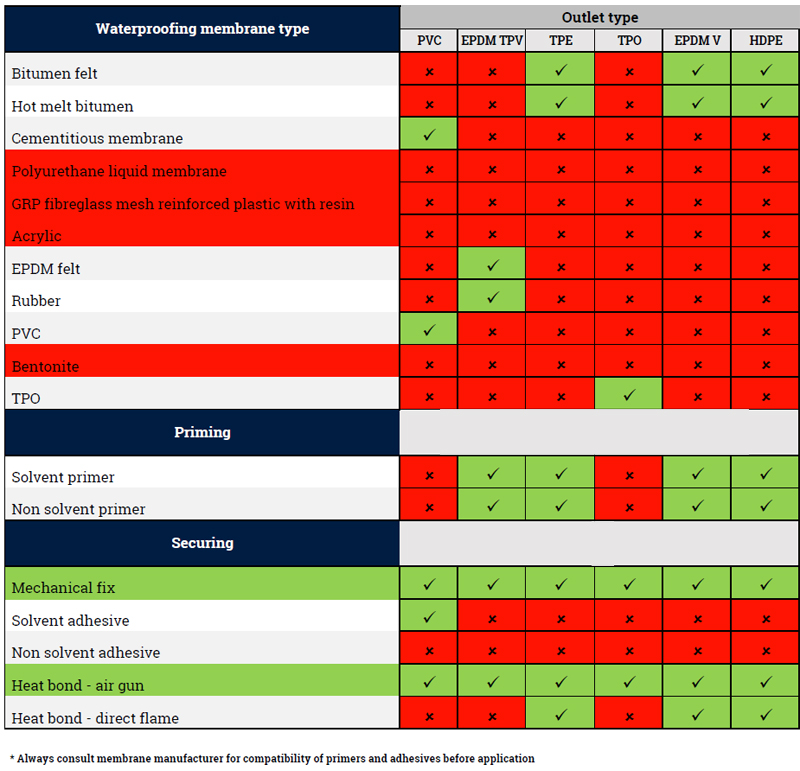

The two other green roofs provided designers with valuable lessons related to the long-term viability and ongoing maintenance. For one thing, green roofs with plantings require robust—and leak-proof—irrigation systems. The elements are tough on a rooftop, so plantings need to be watered accordingly. Another consideration, Rodgers says, involves the potential for invasive plant species to put down roots—quite literally—where they don’t belong.

“One of the easiest examples is a cottonwood [tree],” he explains. “[The] tap root has a way of getting deep, quick, and can get its way through any minor flaw in the way that the [irrigation system’s] water membranes are applied to the roof’s surface. So, if you’re at ground level and exposed, like Daniels’ green roofs are, you have to be thoughtful that those kinds of seeds could blow in and try to grow.”

For the full article, please click here.