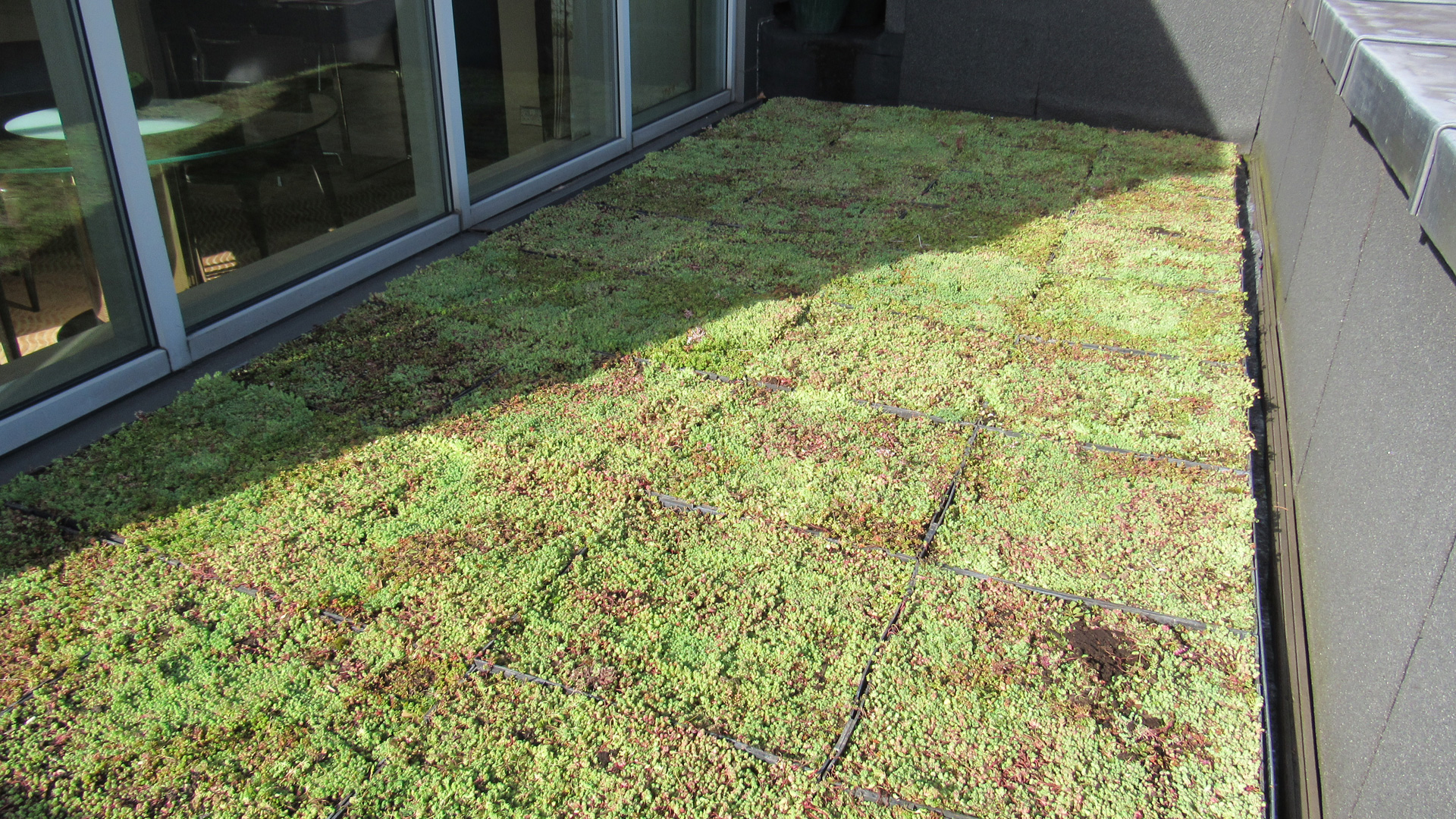

If you walk up to the roof of a social-housing apartment building in Amsterdam, you’ll see a sprawling garden covered in plants. Hidden under the flowers and grass is an extra layer: a thin reservoir that can store rainwater in storms.

Down the street, the same water-storing technology sits under another rooftop garden. It’s also installed on multiple other buildings in flood-prone Amsterdam neighborhoods. The city now has a network of “blue-green” roofs—designed to boost biodiversity, keep buildings cooler in heat waves, and help deal with increasingly frequent extreme rain.

The city government in Amsterdam started looking for new ways to deal with rain more than a decade ago, after a storm in Copenhagen dump around six inches of rain in less than two hours, leading to severe flooding. Climate change is making heavy rain more likely, and the traditional sewer systems in most cities can’t keep up. Amsterdam’s government considered places to add new green space to help capture rain. But in a city that’s already densely built, there wasn’t much room for new parks.

City leaders started asking a new question: “How can we make better use of the buildings that exist—and groups of buildings—to capture and store more rainwater?” says Brian Schmitt, an account manager in urban climate resilience design and engineering for Wavin, a business group at Orbia, the company that makes the blue-green roof technology.

How a blue-green roof works

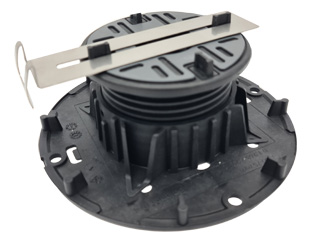

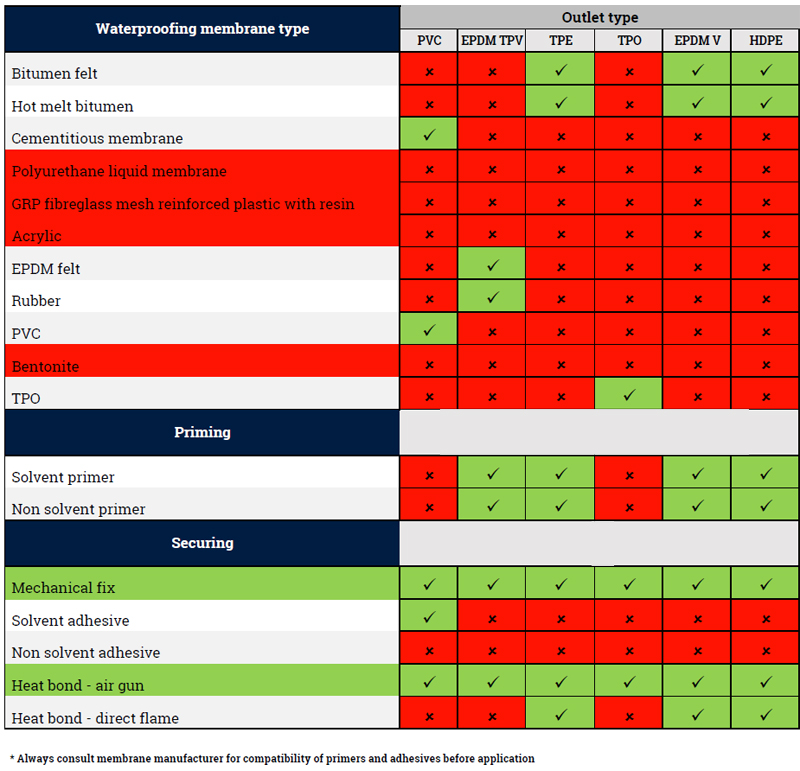

A typical green roof, with a thin layer of vegetation, can also store some water when it rains. But if it keeps raining, or in a heavy storm, the water washes off. A blue-green roof system includes a retention unit under the plants and soil. The system connects to weather forecasts. If rain is expected and the reservoir is already full, a valve can automatically open to slowly let water out in advance, making room for more.

One study found that the technology can capture between 70% to 97% of the rain in that falls on a roof in an extreme storm. A basic green roof, by contrast, can only capture around 12% of the rain. “You are capturing more water and you can monitor how much you are storing at any time,” Schmitt says. By keeping rain on rooftops, it’s less likely that the sewer system will overflow and flood streets. Amsterdam’s water agency used Autodesk software to model the benefits in a particular neighborhood. While a single roof wouldn’t make a huge difference, the team found that if all the suitable roofs were converted, flooding could drop by 60%.

Rain is a major challenge in the area. The first six months of 2024 were the wettest on record for the Netherlands. Over the next three decades, more than a quarter of properties in Amsterdam are at risk of severe flooding. As in other regions, weather whiplash is also a problem: heavy rain can quickly be followed by drought, or vice versa. The technology can also help by holding water when it isn’t raining, slowly wicking water up to the rooftop plants to keep them alive.

The rooftop systems “become squeezable sponges: they retain water in periods of drought and heat, and squeeze and create storage with expected rainfall,” Kasper Spaan, a climate adaptation specialist at Waternet, Amsterdam’s water agency, wrote in a report about the city’s first tests of blue-green roofs.

In hot weather, water evaporates through the plants, helping cool the surrounding area. (If plants die, green roofs lose most of their cooling power, Schmitt says.) With the new blue-green roofs, if extra water has to be released before a storm, it flows down to the city’s sewer system. But the technology can also be connected to cisterns to provide water for landscaping on the ground, or even to help flush toilets inside the building.

Scaling up

In a pilot project called Resilio, completed in 2022, the government helped fund the installation of the tech on several social-housing apartment buildings. They focused on neighborhoods that were especially likely to flood, and on buildings with aging roofs that were already in need of replacement. In total, the project converted more than 100,000 square feet of rooftop space. The project cost €6 million (around $6.6 million), with an 80% grant from an EU urban innovation program.

To read the full article, please click here.