Cassiano and his mother, then 82, had lived in the same narrow four-story house since they moved to Parque Arará, a favela in northern Rio, some 20 years earlier. Like many other homes in the working-class community — one of more than 1,000 favelas in the Brazilian city of over 6.77 million — its roof is made of asbestos tiles. But homes in his community are now often roofed with corrugated steel sheets, a material frequently used for its low cost. It’s also a conductor of extreme heat.

While the temperatures outside made his roof hot enough to cook an egg — Cassiano said he once tried and succeeded — inside felt worse. “I only came home to sleep,” said Cassiano. “I had to escape.”

Parque Arará mirrors many other low-income urban communities, which tend to lack greenery and are more likely to face extreme heat than their wealthier or more rural counterparts. Such areas are often termed “heat islands” since they present pockets of high temperatures — sometimes as much as 20 degrees hotter than surrounding areas.

That weather takes a toll on human health. Heat waves are associated with increased rates of dehydration, heat stroke, and death; they can exacerbate chronic health conditions, including respiratory disorders; and they impact brain function. Such health problems will likely increase as heat waves become more frequent and severe with climate change. According to a 2021 study published in Nature Climate Change, more than a third of the world’s heat-related deaths between 1991 and 2018 could be attributed to a warming planet.

The extreme heat worried Cassiano. And as a long-time favela resident, he knew he couldn’t depend on Brazil’s government to create better living conditions for his neighbours, the majority of whom are Black. So, he decided to do it himself.

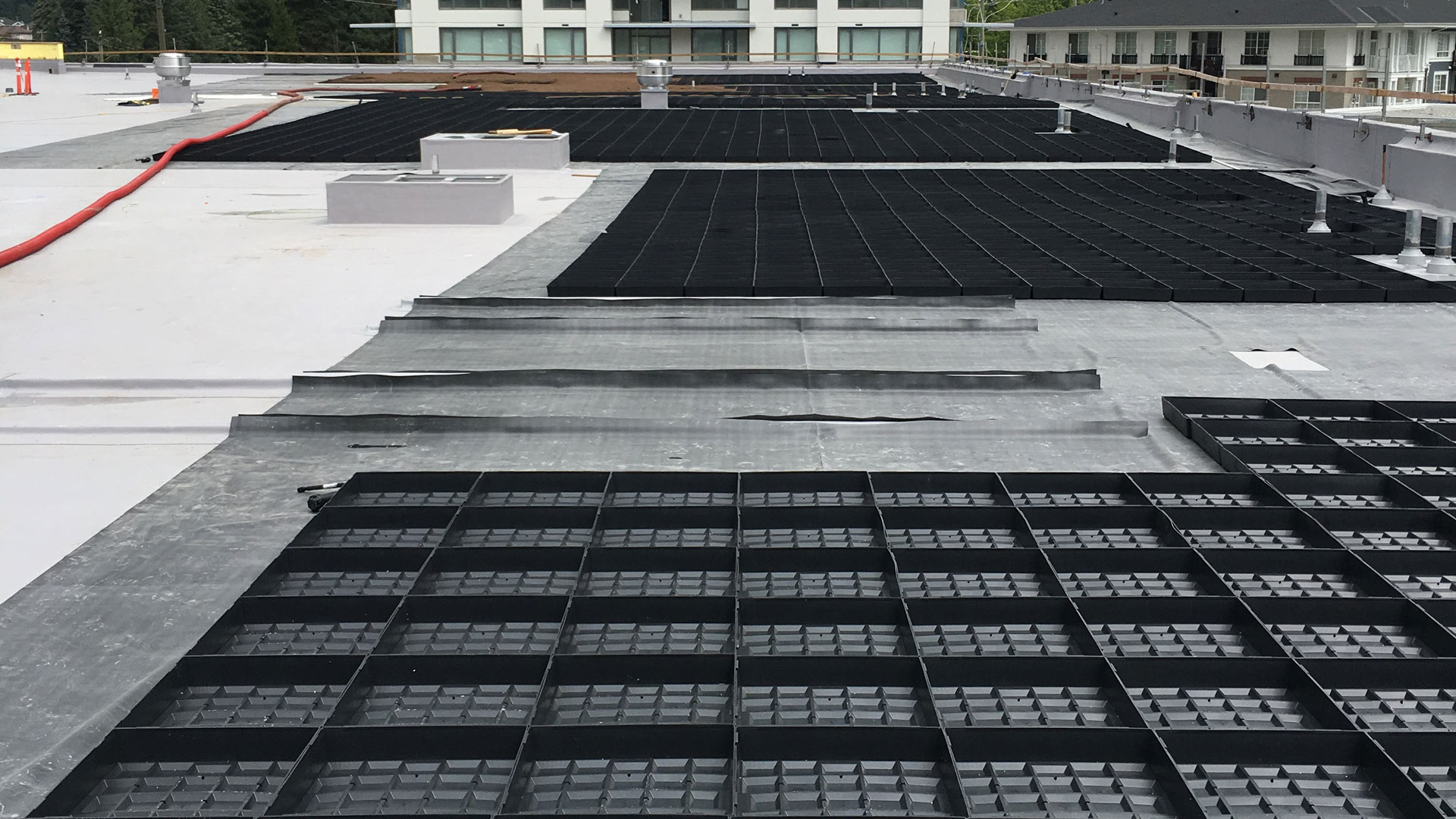

While speaking with a friend working in sustainable development in Germany, Cassiano learned about green roofs: an architectural design feature in which rooftops are covered in vegetation to reduce temperatures both inside and outdoors. The European country started to seriously explore the technology in the 1960s, and by 2019, had expanded its green roofs to an estimated 30,000 acres, more than doubling in a decade.

“Why can’t favelas do that too?” he recalled thinking.

Scientific research suggests green infrastructure can offer urban residents a wide range of benefits: In addition to cooling ambient temperatures, they can reduce stormwater runoff, curb noise pollution, improve building energy efficiency, and ease anxiety.

For the full story, please click here.