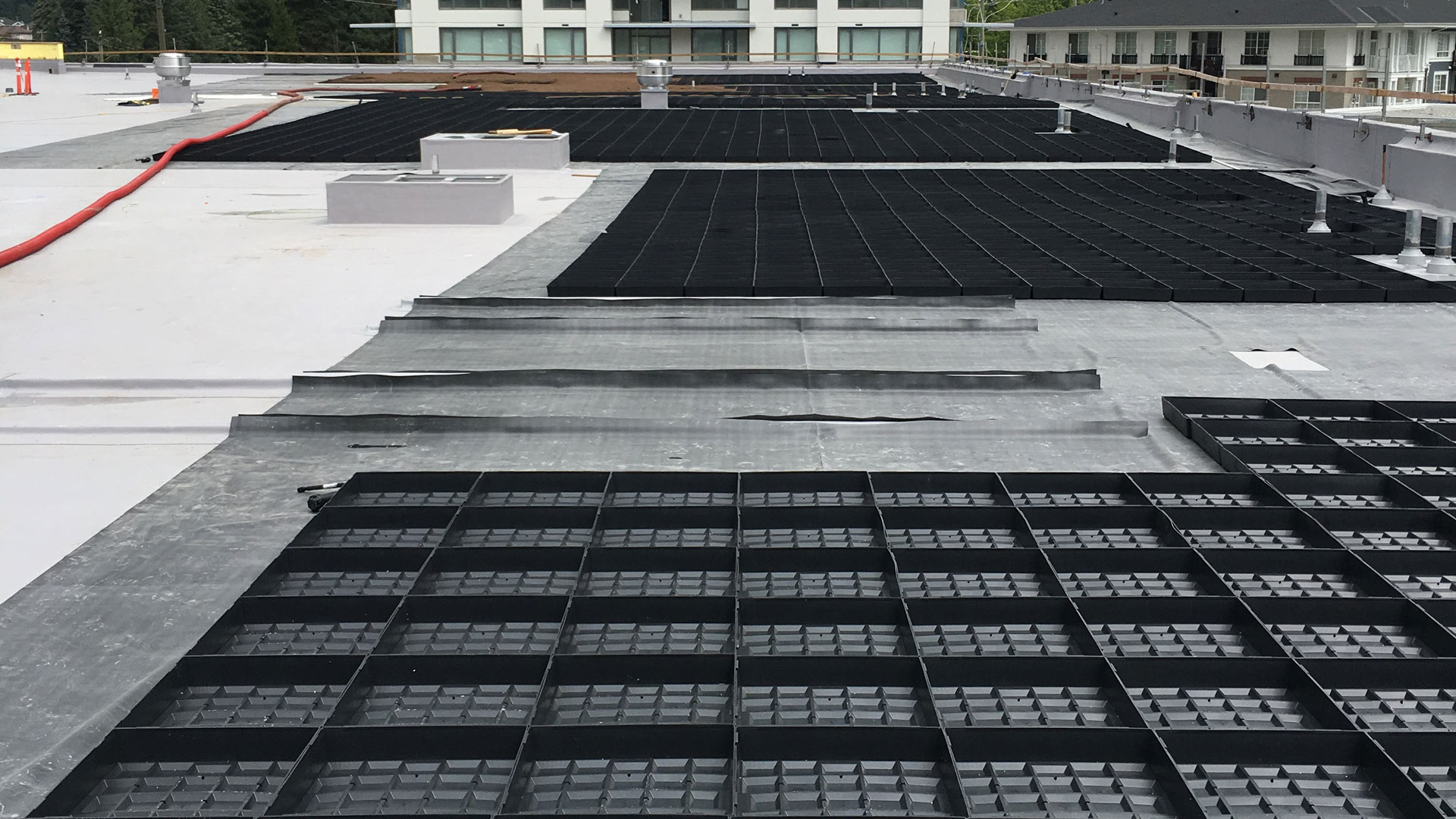

Rio de Janeiro, Feb 25 (efe-epa).- It is summer in Rio de Janeiro and the heat in the narrow alleys of the city’s favelas is suffocating. Cooling these neighbourhoods sustainably is the goal of Techo Verde Favela, a project that was born in the heart of these Brazilian shantytowns.

Also known as aerial gardens, green roofs are considered ‘urban lungs’ that can help improve air quality and biodiversity in cities where cement prevails and vegetation is dying out.

Luis Cassiano, founder of Techo Verde Favela, discovered these benefits six years ago, after suffering from stifling summer heat at his home, one of many in the densely populated Parque Arará neighbourhood.

The favela, home to some 9,000 people living in cramped conditions without access to green areas, is located in the northern part of Rio on land that years ago was a mangrove swamp.

A lover of plants and nature, in green roofs Cassiano found the solution to his problem. After studying in-depth, he started planting his own garden on the roof of his house.

Since then, the small ‘urban jungle’ that sprawls over his home, composed of bromeliads, cacti, succulents and even palm trees, provides him with an escape and a sense of well-being that he had not known before.

“I don’t know how to live without that roof,” Cassiano tells Efe, who, at 51 years old, confesses that he would have gone crazy without the freshness that this garden provides him every day.

“Its greatest importance lies in how it achieves the temperature difference. I’m a person who feels the heat a lot and without that roof, I wouldn’t be able to live here. When I started it, I did it for relief, because I couldn’t stand coming home from work and having all that heat in here,” he says.

After experiencing firsthand the virtues of his green roof, Cassiano wants to replicate the idea in other homes in the community.

The benefits of the roof garden are multiple: it helps prevent flooding, improves air quality, helps reduce energy consumption and turns concrete and brick structures into “more beautiful”, breathable spaces.

According to the environmentalist, promoting the implementation of these roofs in the favela has not been easy, because these kinds of projects are long-term and people want “immediate results.”

Added to that is the daily care — and costs — needed for their upkeep. Residents of the favela are less inclined to fund what many see as a luxury during a pandemic that has left many without work.

To overcome doubts about the costs and benefits of the gardens, Cassiano insists that environmental education and passion for all things green is key.

“The person has to know what they are doing, but they must also love plants,” he says.

But because of restrictions related to the pandemic, work with the community to get them engaged with the project and teach them about its benefits was abandoned, and will only be resumed once the risk of contagion has been addressed.

It is “robust” work, Cassiano says, which is done with the heart and survives on voluntary help, which is increasingly scarce.

Projects like Techo Verde Favela have also seen financial support from the municipal government dry up because of Covid, with funds to rebuild the city’s struggling commercial center and to save some 800,000 jobs being prioritized over longer-term environmental goals. EFE/EPA

Please click here for the full article.